The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has triggered a data center gold rush. Since the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, hundreds of billions of dollars have already been spent on constructing new hyperscale and colocation facilities. But the industry’s explosive growth now faces a reckoning–communities are pushing back. Questions on impacts to water supplies and electric power prices are now the topic du jour in town hall meetings discussing local data center developments.

In October 2025, following opposition from industry groups, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed legislation (Assembly Bill 93) which would have required California data center operators to share site level water use estimates and annual consumption reports with local water suppliers. The rejection underscores a national challenge and may well be a missed opportunity. Thus far, the breakneck pace of data center development has outpaced the public’s understanding of water’s role in AI. Regulation lags even further.

The data center industry is at a critical inflection point regarding its social license to operate—particularly when it comes to water. Will companies meet the moment through transparent, credible public messaging and measurable water stewardship actions, or miss the mark?

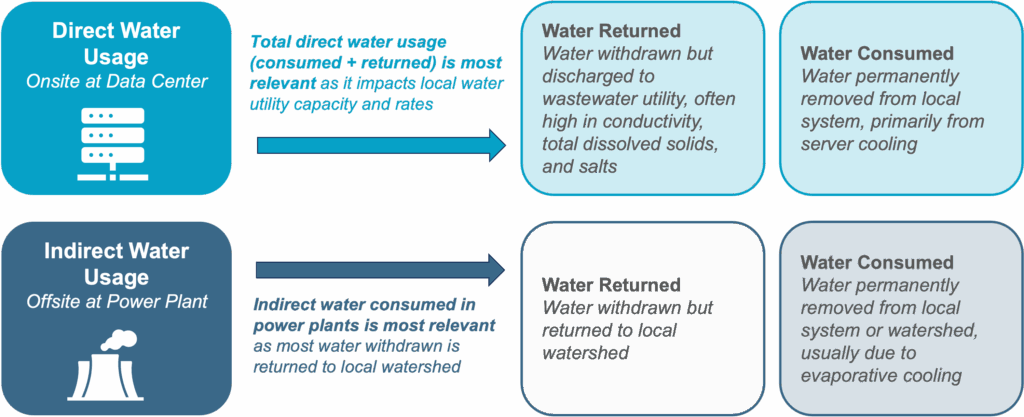

The true water footprint of data centers: direct on-site usage AND their indirect water usage at power plants. Bluefield’s data center market trends report estimates that in 2025, U.S. data centers will directly withdraw 107 million gallons of water per day (MGD) and consume approximately 60% of that water (62 MGD), primarily due to cooling needs. Considering that accounts for a mere 0.5% of total direct industrial water consumption in the U.S., the direct water usage for data centers appears quite insignificant.

However, when accounting for indirect usage (water attributed to data center electricity demand at thermoelectric power plants), the number balloons. According to Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, in 2023 data centers accounted for 211 billion gallons (578 MGD) of indirect water consumption at power plants—nearly ten times that of on-site data center water consumption for the same year. Heightening this challenge is the rapid growth of electricity demand by data centers, which has been forecasted to grow from 4% of total U.S. electricity demand in 2023 to as high as 12% in 2028.

Many data center operators, including major tech companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta, have self-imposed goals of becoming water positive by 2030. This means they aim to invest in local community projects like watershed restoration and clean water initiatives to return as much water as they use. But these targets ignore the far larger water footprint embedded in their outsized electricity use, which the operators are acutely aware of. For example, a leaked Amazon internal memo showed the company strategized to downplay its indirect water use and avert scrutiny prior to its 2022 water positive campaign launch.

Data centers impact community water supplies via both on-site usage and indirectly via thermoelectric power plant water consumption.

To fully capture the true snapshot of a data center’s water impact, indirect water usage must be included. Certainly, this responsibility does not fall exclusively on data center developers, but the cumulative impact at the basin level from both onsite water usage and the electric power sector cannot be ignored. Look no further than states like Virginia, where data centers already account for 26% of the state’s total power demand.

Useless high-level reporting or useful on-site data? The real water data dilemma. Water is inherently local, and the impact of a data center varies heavily based on its size, cooling methods, and geography. Local planners are challenged to forecast water supplies despite market uncertainty and inconsistent transparency from data center operators.

As such, the industry is stuck in a Catch-22. Site-by-site water usage would help clarify local impacts, but that same facility-level water usage is more often considered proprietary.

When the Texas State Water Board surveyed operators to self-report their data center water usage to support state-wide planning, only a third of operators responded. Nevertheless, pushes for greater transparency continue. In Oregon, a lawsuit forced Google into partial disclosure, ultimately revealing that the hyperscaler directly used 355 million gallons of water at its Dalles data center in 2021—more than a quarter of the city’s total supply.

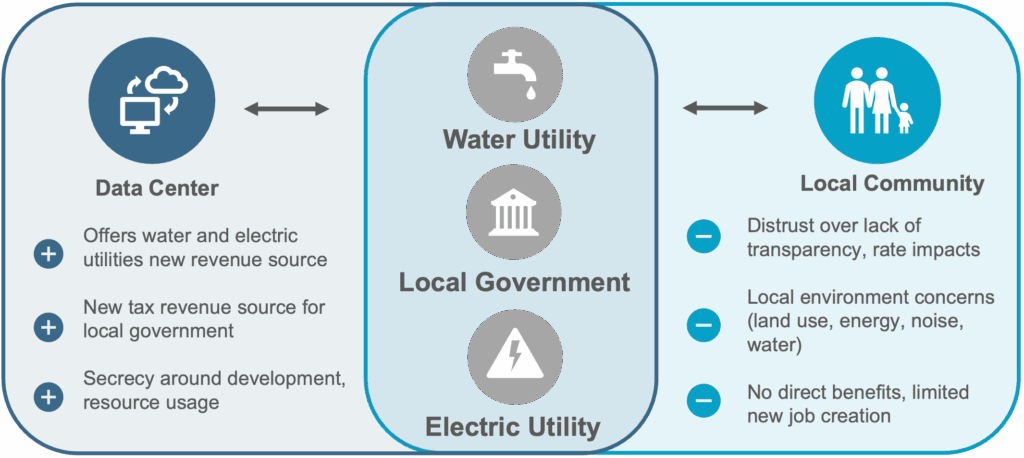

With approximately 97% of data centers relying on municipal water supplies and services, secrecy leaves utilities and planners flying blind. Without clear site-level data, local communities can’t assess the true trade-offs between jobs, tax revenue, rates, and long-term water security.

Water utilities, local governments, and electric utilities must balance potential benefits of data centers with local community concerns.

Utility mistrust is an unintended consequence. Depending on where one looks for confirmation bias, reports from the Harvard Electricity Law Initiative and the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis indicate that electric utility ratepayers are subsidizing data center buildout. In parallel, public statements from electricity providers promise the opposite–that data centers themselves have no impact on electricity rates. These polarized perspectives highlight the problem, that it is virtually impossible to convince ratepayers that they are not bearing an inequitable cost share of the data centers boom.

Water utilities face similar challenges like their electric utility counterparts. Public trust in water utilities has slipped from 77% in 2022 to 74% in 2024, according to survey work commissioned by the American Water Works Association. Inflation is making water rate increases difficult, and credit rating agencies have cited the inability to pass rate increases as a growing water sector challenge. As water ratepayers suspect that utilities favor large corporations over residents, opposition to new projects and rate increases hardens. Rebuilding that trust will require greater transparency around pricing, infrastructure investment, and cost allocation.

Almost overnight, data centers have taken center stage at the intersection of growth and accountability. The choice seems clear: embrace transparency or lose the social license to operate. For data centers to truly be water-positive, they must first be information-positive about the full extent of their impact.